In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

It is summertime, which I have always found to be the best time to read pulp adventures—the pulpier, the better. Whether it is space opera or planetary romance, there is an energy to pulp stories that can hold your attention even when the distractions of a sunny day surround you. Today, I’m taking a look at the third book in E.E. “Doc” Smith’s seminal Skylark series, Skylark of Valeron. I thought it would be a good one to read while bobbing around my above-ground pool in a rubber raft, enjoying the weather. But unfortunately, Smith’s urge to constantly outdo himself with ever grander ideas got the best of him, and this is a book that didn’t stick the landing.

Skylark of Valeron, which appeared in Astounding in 1934 and 1935, is the sequel to The Skylark of Space, which debuted in Amazing Stories magazine in 1928 (you can see my review here), and Skylark Three, which appeared in Amazing Stories in 1930 (you can see my review here). There was also one more book in the series, the much later (about three decades later!) Skylark DuQuesne, which appeared in Worlds of If in 1965.

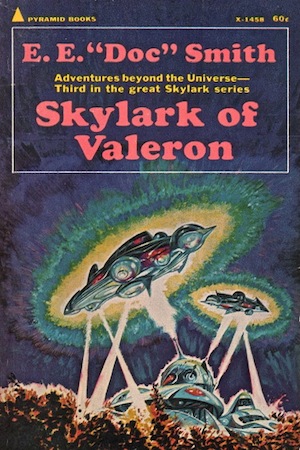

The copy of Skylark of Valeron I reviewed is a reissue from Pyramid books, a second paperback edition published in 1966. The cover is another impressionistic painting by Jack Gaughan, who had also illustrated Pyramid’s reprints of Smith’s Lensman series and the other Skylark books. While not as evocative as Gaughan’s other covers, it captures a lot of pulpy energy, matching the book it adorns.

I’ve previously reviewed Smith’s entire Lensman series, including Triplanetary, First Lensman, Galactic Patrol, Gray Lensman, Second Stage Lensmen, Children of the Lens, and Masters of the Vortex. Once again, as with the Lensman books, I must thank Julie at Fantasy Zone Comics and Used Books for finding this book for me.

About the Author

Edward Elmer Smith (1890-1965), often referred to as the “Father of Space Opera,” wrote under the pen name E.E. “Doc” Smith. I included a complete biography in my review of Triplanetary. Like many writers from the early 20th century whose copyrights have expired, you can find quite a bit of work by Doc Smith on Project Gutenberg, including The Skylark of Valeron.

Expanding Stories

Sometimes, either deliberately or seemingly on their own accord, stories will grow both in length and in scope. An author will write a work that is so long publishers will break it into multiple volumes, as was done with one of the first trilogies I ever read, The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien. But more often than not, authors who write a series or trilogy often do not originally set out to do so. The first volume is frequently a story that stands by itself. Part of this is economic, as it is not prudent to set out to write multiple books before you know the first one will be popular. A modern example of this is the original Star Wars trilogy. The first movie, Star Wars (now known as A New Hope), was intended to tell a complete story (though Lucas had conceived of a much larger story in his early drafts), but its wild popularity allowed George Lucas to go further. He had in mind a story that would require at least three installments (if not more) to tell, and was audacious enough to leave the second movie, The Empire Strikes Back, with a cliffhanger ending, which was not resolved until the next film, Return of the Jedi. While that had been a common occurrence in the movie serials that inspired him, it was quite a shock to moviegoers of the 1980s, who were not used to the practice. I was reminded of Star Wars when I read the third volume of Doc Smith’s Skylark series. Like Star Wars, that series started with a volume complete in itself. The next volume, however, ended on a cliffhanger, with the heroes starting off on a long journey, and the fate of the villain left as a loose thread. So it was up to the third volume to bring the story to a close.

There is another element of the Skylark series that reminded me of Star Wars, and that is the way the scope and stakes of the stories escalate over time. Doc Smith is famous, both in his Skylark series and in the Lensman series, for presenting bigger and bigger scientific discoveries, grander spaceships, more destructive battles, and increasingly menacing foes. In fact, I would say it’s a tendency that Smith takes to a fault. The scope of the Lensman series grew until whole planets and even stars were being destroyed. And in the Skylark series, not only is each new Skylark ship larger than the last, but Dick Seaton faces ever fiercer foes until he meets immaterial beings who can bend reality to their will. There is a concept called “suspension of disbelief,” always important in science fiction, which involves convincing the readers to accept elements of the story that they might otherwise reject. And unfortunately, Smith’s stories often became so grand that the sheer scope undermines the reader’s suspension of disbelief, and becomes implausible.

The Star Wars series follows a similar arc. The first Star Wars movie introduced a giant space station, the Death Star, which the rebellion attacked with small fighters. By the third movie, an even bigger space station, the Death Star II, was the center of a conflict between dueling fleets of capital ships. And the scope grew even grander in the newer Sequel Trilogy, where the first movie introduced a planet that’s been turned into a giant battle station capable of destroying multiple planets simultaneously, and the third introduced a whole fleet of ships with planet-killing weapons. The cost of building such a battle fleet was not addressed, probably because it would not just threaten the necessary suspension of disbelief, but would shatter it completely. It turns out that in storytelling, bigger is not always better.

Skylark of Valeron

The book picks right up where Skylark Three left off, or actually before the end of that previous book. If you wondered what happened to Blackie DuQuesne and his henchman “Baby Doll” Loring, who had been heading for the world of Fenachrone just before Dick Seaton and his allies blew it up, you get your answer here. DuQuesne has a Fenachrone officer he rescued from space, and a mind-reading machine that can transfer all the memories from the alien to his own brain. He and Loring then employ that knowledge to capture a Fenachrone battleship, which he plans to use to conquer the Earth. DuQuesne detects the destruction of the Fenachrone home world just in time to escape the blast wave, and sets out to find the alien race that gave his foe Seaton the power to destroy an entire planet.

Dick Seaton and company (including his wife, Dorothy, his friends Martin and Margaret Crane, and their faithful but barely mentioned valet, Shiro), had in previous volumes, after repeated assassination attempts by DuQuesne and his allies, decided they were all safer traveling in space than staying on Earth. After bringing peace to the world of Mardonale, Seaton had worked alongside (and even swapped memories with) the advanced scientists of Norlamin to learn the secrets of higher orders of reality, all the way up to the sixth order, an order of thought. He and his friends then boarded their ship, Skylark Three, used that knowledge to destroy the home planet of the evil and repulsive Fenachrone, and pursued and destroyed a ship full of Fenachrone dissidents who were trying to escape to a distant galaxy.

Next, Seaton and his companions decided that, rather than waste the velocity they had built up, they would visit that far-flung star system. But as this volume joins them, they encounter disembodied energy creatures called “the pure intellectuals,” who board the Skylark Three without regard for physical bulkheads, and want to disembody Seaton and his friends. In desperation, the crew boards the smaller Skylark Two as a lifeboat, and Seaton uses his expanded powers to shift them into the fourth dimension.

Meanwhile, DuQuesne finds the planet of the Norlaminians, presents himself as a friend of Seaton, and tricks them into sharing with him the scientific secrets they’d previously shared with his foe. With that knowledge in hand, he and Loring head home to Earth to conquer the world.

In the fourth dimension, the crew of the Skylark Two are separated, and Seaton and Margaret have to fight their way across a strange plane of existence to rejoin the others. And when Skylark Two returns to the normal three-dimensional world, they find themselves so far away from home that they can’t locate the Earth, or any of the worlds they have visited. They look for a planet they can use as a base to build a detector powerful enough to find their way home, and stumble across the human-inhabited world of Valeron, which is under attack by the evil, chlorine-breathing amoebic creatures called the Chlorans.

Smith then takes us on a long digression that describes the conflict between the Valeronians and the Chlorans, whose world had been deposited into the solar system of Valeron when its star passed too close. They had then waged a long war, which the humans had been slowly losing, until only one crowded city remained, huddled under a weakening force field. But the arrival of Seaton gives the Valeronians the knowledge they need to build advanced defenses that use the forces of the higher orders of reality, and soon the Chlorans are defeated.

Seaton then uses the resources provided to him by the grateful Valeronians to begin building a new Skylark ship. Dorothy convinces him to abandon his old system of numbering ships, and they christen her the Skylark of Valeron. Seaton builds a giant computing device, something we might now refer to as an artificial intelligence, which is at the heart of the new ship, and finishes the construction process itself. The new ship is huge, a sphere a hundred kilometers in diameter that masses millions of tonnes. In a move much more merciful than his destruction of the Fenachrone, Seaton uses his new ship and its powers to place the Chloran planet back into its home solar system, securing safety for the Valeronians, and displaying the mighty powers now at his disposal. Then, having built the ship around a giant detector, Seaton and his comrades map the universe and locate the Green System, the home of their friends on Mardonale and Norlamin.

At this point, there were only a few pages left in the book, and I found myself fearing a rushed conclusion. Unfortunately, I was right. The crew of the Skylark of Valeron again encounters the pure intellectuals, and this time the once-fearsome foe is no match for their new powers. When Seaton and company turn their attention to freeing Earth from the clutches of DuQuesne, conveniently sweeping aside the immense power their foe has amassed as if it were nothing, the story reaches a conclusion that is more anticlimax than thrilling ending.

Final Thoughts

Skylark of Valeron could have been another fun adventure in the series, but unfortunately, by trying to outdo the preceding volumes, Smith takes his fictional technology to a level where it works to the detriment of the story rather than enhancing it. An author can boggle the reader’s mind with wonders, but can also take things to the point where the hero is so powerful that the story loses all believability.

Now it’s time for you to join the conversation, and provide your thoughts on Skylark of Valeron in particular, the rest of the Skylark series, or “Doc” Smith’s work in general. And as always, if you have any other space opera adventures you want to discuss, especially those that make good summer reading, the floor is open.